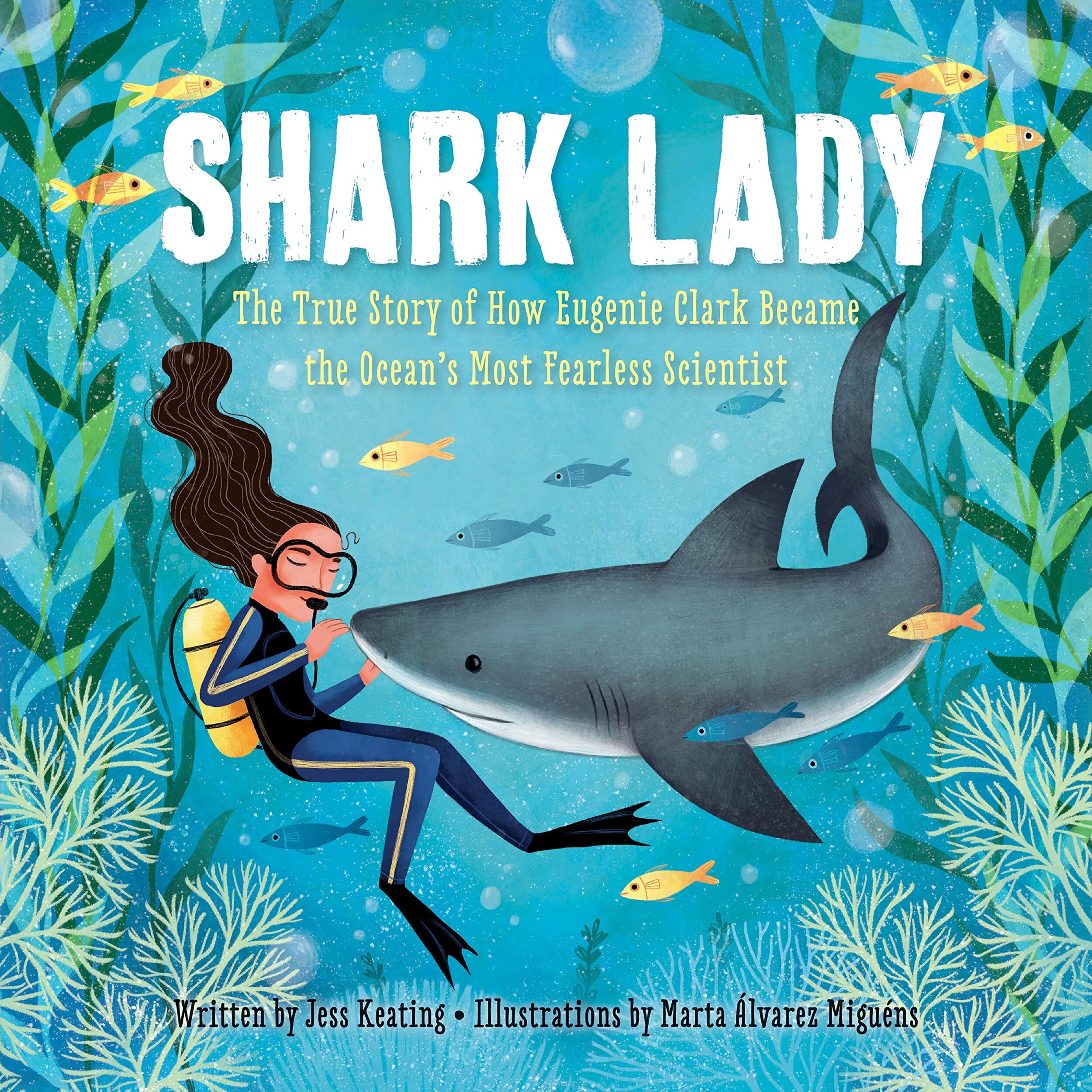

Shark Lady: The True Story of How Eugenie Clark Became the Ocean’s Most Fearless Scientist

Keating, Jess. Shark Lady: The True Story of How Eugenie Clark Became the Ocean’s Most Fearless Scientist. Illus. by Marta Alvarez Miguens. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2019.

Eugenie Clark (1922-2015) began her love affair with sharks at the age of nine years, when she first visited the New York Aquarium at Battery Park in 1931. Making the most of her vivid imagination on this occasion, she pretended that she was walking on the bottom of the ocean where she could dream of swimming with sharks. On later trips to beaches in Atlantic City she dove as deeply as she could and marveled at the incredible diversity of marine life. Next, she dove into books in order to learn all that she could about such species as whale, tiger, nurse, and lemon sharks. Eugenie kept notebooks filled with shark facts. She became the youngest member of the Queens County Aquarium Society. Her mother always encouraged her daughter’s fascination with ocean studies and presented her with a 15-gallon tank aquarium that was far too small for sharks, but became her first personal laboratory.

Eugenie wanted to study zoology, despite the protests from male college professors who believed that women could not become great scientists and did not possess the bravery that ocean exploration required. She broke through every possible gender barrier she confronted in a very long and exceptionally distinguished career. She earned her bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees in zoology between 1942 and 1950. Her scholastic success was great enough to also earn her a scholarship to study fish in the Red Sea, where she discovered three marine species previously unknown to scientists.

Earning a research mission to explore the Palua Islands in the western Pacific Ocean, Eugenie first encountered wild sharks. She devoted her life to the discovery of new knowledge about sharks and to dispel unfounded myths about them, especially that they were dangerous killers. Her studies proved that the more than 400 species of sharks are far more intelligent and much less of a danger to humans that other marine zoologists had formerly believed.

The primary focus of Shark Lady highlights Dr. Eugenie Clark’s scientific accomplishments, but a companion story thread relates how one very courageous woman triumphed in an academic world that had previously been totally dominated by men.

Jess Keating’s fine narrative of Eugenie Clark’s life is crowned by two vibrant double-page spreads. “Shark Bites” shares valuable facts about sharks, her life’s great passion. Readers learn, for example, that the skin of sharks is composed of dermal denticles that are more like teeth than the scales of fish. This unique skin allows sharks to swim extremely fast. Swimsuit designers have utilized this discovery by Dr. Clark to create swimwear to help world-class swimmers have a competitive edge in aquatic events in the Olympics. A brightly illustrated “Eugenie Clark Time Line” traces the remarkable and long life of this great marine biologist.

Marta Alvarez Miguens’ bright cartoon-style illustrations beautifully complement both the key narrative and the end matter of Shark Lady. Realistic drawings of many species of sharks and other marine life enhance the end pages of the book.

Dr. Jerry Flack is Professor Emeritus and President’s Teaching Scholar Emeritus at University of Colorado, Colorado Springs.

Home Activities

What’s in a word? No doubt because Shark Lady was created for younger readers, the most challenging word to describe Dr. Eugenie Clark’s life work is “zoology.” Students who engage in further research about this remarkable scientist will discover that she is often referred to as an “American ichthyologist.” Ask children to research the word “ichthyology.” What is its current meaning and what is its etymology? What other words or terms, such as “marine biology,” may be used to describe the world of exploration of this great scientist?

Dr. Eugenie Clark was one of the most renowned marine zoologists and women scientists of the 20th Century. Encourage students to read about additional scientists such as Rachael Carson, Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Jacques Cousteau who conducted breakthrough research in lifetimes that at least partially paralleled the career of Dr. Clark. Following such inquiries, encourage children to create an illustrated Venn diagram revealing the positive similarities and unique differences of Dr. Clark and perhaps Jacques Cousteau or Jane Goodall.

When she was nine years old, Eugenie Clark’s mother presented her with an early Christmas gift of a 15-gallon aquarium in which she housed guppies, clown fish, and coral-red snails. Biographer Jess Keating refers to this gift as more than an aquarium. It was also a laboratory and a sanctuary for a young gifted girl. Ask readers to write a thank-you note that young Eugenie might have written to her mother explaining why her personal aquarium is a “sanctuary.”

The life span of Dr. Eugenie Clark (a.k.a. the “Shark Lady”) was almost 93 years. If she had remained alive, she would be 100 years old in 2022. Using the pleasing illustrations of Shark Lady as a model, invite students to design a century landmark birthday card for this great ichthyologist. How might children salute the life work of a brilliant scientist whose legacy was her study the 400 plus species of sharks found in the world’s seas and oceans? One alternative would be to create a special postal stamp to honor Dr. Clark’s life.

Keating, Jess. Shark Lady: The True Story of How Eugenie Clark Became the Ocean’s Most Fearless Scientist. Illus. by Marta Alvarez Miguens. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2019.